The CHIPS Act presents a compelling opportunity for American research universities to collaborate in a nationwide initiative to produce innovation and chip manufacturing capacity. Making the most of it relies on comprehensive analysis and planning.

“We need more than funds from the federal government, we need strategic focus,” said Shirley Ann Jackson, the President of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute earlier this year in a North American University President’s forum on the Evolving Role of Universities in the American Innovation System. And in August, the CHIPS Act delivered exactly the sort of scientific challenge that can provide the focus that had been lacking in America. Formally known as the ’Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act of 2022,’ the CHIPS Act received unheard of bipartisan support, passing through both the U.S. House and Senate, with the Senate voting 64-33 for passage.

The CHIPS Act is a straightforward combination of national security and economic policy that Americans are finding easy to rally behind. The bill formalizes a large federal investment in semiconductor manufacturing and research and development to boost U.S. competitiveness, innovation and national security.

An American science policy with impact

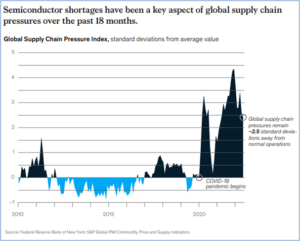

CHIPS Act represents a national science policy with concrete objectives and the funding, strategy and planning to lead to success. Just as the end of World War II and the launch of Sputnik created a sense of purpose for U.S. science policy, here we have a similar level of commitment and purpose – a real and urgent national goal tied to the investment of billions across multiple years to address it. The US government is investing to create a domestic supply-chain for semiconductors and electronics after having witnessed the havoc wrought on the US economy due to the supply chain disruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic. (See Figure 1)

In this case, the American government is working to create innovative and secure chip research and manufacturing capacity within its borders. The CHIPS Act uses federal dollars as a catalyst to encourage R&D and translational work, tapping into the combined expertise of universities, industry partners and states working collaboratively to produce innovation and chip manufacturing capacity.

FIGURE 1 – The problem in brief – The global economic problems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic showed the economic and security vulnerabilities posed by supply chain disruptions.

Source: The CHIPS and Science Act: Here’s what’s in it. McKinsey and Company, Oct 4, 2022;

Turning pronouncements into actions

According to a report from McKinsey & Company, there are specific provisions for allocating the investment of $280B over the next ten years, including four principal mechanisms to channel funds to U.S. academic institutions.

- $11B for academic research – The National Science Foundation (NSF) will oversee the distribution of $11B in new grants to be distributed over the next five years through a newly created National Semiconductor Technology Center.

- The President’s Council of Science and Technology Advisors recommends these funds be concentrated in six ’Coalitions of Excellence’ that are meant to be innovation/collaboration hubs with industry and regional development.

- $14B for basic scientific research – The Department of Energy (DOE) will be allocated an additional $13B across the next 5 years – $2.5B/year for investment into ’basic science’. This will swell the existing DOE research budget to $50B. In addition, there is an additional $1B to be invested in research for low-energy/low-carbon emission steel production.

- $10B for research/infrastructure in 20 regional hubs – The Department of Commerce will be allocated $10B across the next five years to invest in the creation and development of Regional Manufacturing Clusters with these funds being overseen by the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST).

- $200M to create a national microelectronics training network overseen by the Commerce Department in coordination with NSF. This is meant to support “at least 50 ‘hub’ universities and colleges geographically distributed across the country, including minority-serving institutions .”

What does this mean for the American academic research enterprise?

The opportunity for U.S. research universities is historic – the CHIPS Act will boost federal research funding by more than 15% per year, adding roughly $7B/year to a budget of as much as $46B. For university research leadership, the expansion of funding across the agencies opens up questions of focus and institutional objectives. With multiple paths available, where should we compete?

As American universities compete to participate in these initiatives, the first step to developing a CHIPS Act strategy is to complete a realistic assessment of a university’s research strengths and weaknesses. Resources and energy should be concentrated on those areas in which an institution is most likely to win. To help with that winnowing process, the early movers are asking the following questions as part of their campus-wide strategic planning:

- Are we best suited to simply apply for the new basic science grants – biology, chemistry, physics, astronomy – through the expansion of DOE funding?

- Should we lead (or join) a coalition looking to wins a regional manufacturing cluster from the Department of Commerce?

- Are we eligible for the NSF funds focused on innovation in semiconductor research and development?

Of course, budget authorization is not the same as actual funding appropriation. However, some dollars have already been allocated and the bi-partisan nature of the bill implies that funding is more likely than less. As such, the scale of the funding here demands that university executives evaluate and choose a plan of action that can be implemented as soon as funding is approved.

“I think the investments we make should be directed to the areas that have a critical bolus of top-notch science, in a particular area that we can build on.”

Regardless of the specific rules that will be written, the most important and critical factor in winning some of this research funding is the strength of the underlying science taking place in university labs.

Although there is not yet clarity as to the evaluative rubric that will be used for the various programs in the CHIPS Act, the meetings of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) have shed light on the metrics most likely to be used to judge grant applications. In answer to a question “How will you assess what is a good investment?” U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo answered, “First, the quantity and quality of intellectual capital in a region; second, the quantity and quality of research.”

As with all institutional initiatives, a formal strategic plan that begins with assessment, includes goal setting, resource allocation and careful monitoring of progress should be created. To help determine a university’s best plan of action, take the following steps:

Step 1 – Complete a research portfolio disciplinary assessment. Create a full accounting of your institution’s publication record on a discipline-by-discipline basis. By evaluating both the quantity and the quality of the underlying science, it is possible to map an institution’s investigative strengths.

Step 2- Map the university’s strengths/deficits relative to each of National Science Foundation and Department of Energy criteria (as currently understood). Each of the funding appropriations are trying to achieve slightly different objectives, while they all fit under the broad heading of Semiconductor Manufacturing and Innovation – the purpose of every part of the bill . To determine if a school has a better chance of being part of the Innovation Hubs or simply applying for DOE grants, school leaders should do a high-level fitness analysis, measuring things like:

- Geographic – is the institution located in a favorable zone from an economic development perspective?

- Disciplinary/Thematic ‘fit’ within overall map of R&D within semiconductors: How and why does what we do at X University contribute to the overall project?

- Measures of scale/commitment – Volume and recency of publications shows the volume of R&D activity and work on campus

- Innovation hubs – What other attributes of a hub exist? Companies? State funding? Tax incentives?

- Curricular review to determine fit with “National Microelectronics Training Network;” Industry liaison to serve as network connection accelerator

Step 3 – Create a tactical project plan to address highest probability opportunities. To be considered as part of an innovation hub, the institution needs to partner with other universities, companies and state/local leaders. Create the operational working groups and teams, with governance and oversight, to ensure success:

- Find partners/consortium to lead/join

- Identify net new grant opportunities in disciplinary areas of focus, creating mechanisms to push information outward and coordinate responses internally

- Create project plan, marketing pitch, advancement campaigns

The CHIPS Act provides an opportunity for institutions to dramatically expand their research standing. As with most things, success will come to those who are most prepared and focused in their efforts.

ClarivateTM can help you and your teams chart a path forward. Contact us to discuss the CHIPS Act and how Clarivate can help.

References:

The CHIPS and Science Act: Here’s what’s in it. McKinsey and Company, Oct 4, 2022;

The Evolving Role of Universities in the American Innovation Ecosystem. University Presidents Forum – hosted by Duke University March 3, 2022: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GgEI6j9K_c&list=WL&index=21&t=3750s;

Advancing the US Innovation Ecosystem & Innovation Hubs: Implementation of the CHIPS & Science Act. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology – Sept 21, 2022 https://www.whitehouse.gov/pcast/meetings/2022-meetings/

“Regional Innovation Provisions in the CHIPS and Science Act” Tim Clancy, American Institute of Physics, October 26, 2022: FYI: Science Policy (online newletter)