‘Sleeping beauties’: Yesterday’s findings fuel today’s research breakthroughs

Older research often presents fresh opportunities to advance scientific and scholarly research today. Learn more about a few notable examples.

Staying up to date with the newest findings in a field is critical in today’s fast-paced research environment. Researchers need to ensure that they are pursuing novel ideas and incorporating the most recent evidence in their work. In some scientific disciplines, such as medicine, researchers have discussed how a preference toward novelty can go so far as to affect research behavior. The excitement generated by the promise of a new treatment can activate a set of biases. These culminate in an overall ‘novelty bias’ effect—the tendency for new interventions to appear better.

However, tuning in to the newest developments in a field isn’t the only way to surface fresh opportunities. Scientific discovery is a cumulative process. Each researcher builds on the foundational work of previous scholars, not just contemporaries. One study from researchers at Northwestern University found that “works that cite literature with a low mean age and high age variance are in a citation ‘hotspot’; these works double their likelihood of being in the top 5% or better of citations.” High-impact research considers older literature as well as the ways in which new studies improve upon prior research.

Directly exploring older research can reveal concepts and developments that have high potential to advance modern topics. In fact, there are new building blocks waiting to be discovered.

Significance of prior research

In many cases, research progress is built upon foundational theories and methodologies established in older work. Building an understanding of these research cornerstones, the context in which they were created, and how they have evolved can spur new conceptual breakthroughs. Older literature also provides background to support new hypotheses and experiments, prevents unnecessary duplication of studies and often offers up unique observations and data points that may no longer be available.

Consulting older research not only helps in building an authoritative understanding of a topic, but it can also reveal research that was ahead of its time. We’ve seen cases where prior research takes on renewed significance in today’s context. Consider solar cells. They were impractical when they were first discovered in the late 19th century, when they were made of selenium. Further research and advancements led to the development of an efficient solar cell made from silicon in the 1950s.

Several other research fields provide similar examples. The concept of citation indexing, introduced by Dr. Eugene Garfield in the 1950s, strongly demonstrates how an idea continues to transform and shape the world for decades to come. “Garfield anticipated — by 40 years — the advent of hyperlinked pages on the web and the appearance of the Google Search algorithm (the patent for which cites Garfield).” Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in 1916, a theory that was confirmed in 2015 by LIGO researchers. Statistical tools outlined in research papers from the 1930s gained significance when large data sets became available decades later.

The impact of early climate change research

Bibliometric research outlines a phenomenon known as “sleeping beauties” or delayed recognition. Sleeping beauty papers receive only little to moderate attention, via citation, shortly after publication, but they experience a significant spike in research interest years or even decades after their appearance. This phenomenon speaks to the importance of older research and citation indexing.

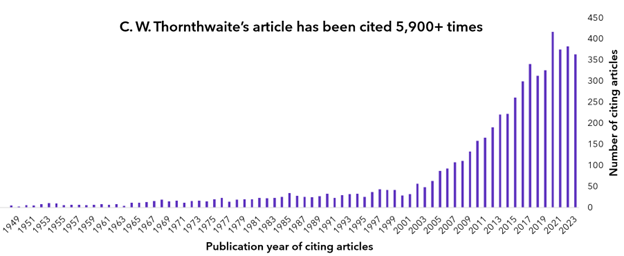

One such paper, “An Approach Toward a Rational Classification of Climate” was published by an eminent American geographer and climatologist, Charles W. Thornthwaite, in 1948. This piece of research received only moderate attention from the research community until the beginning of the 2000s, when citations to this paper grew dramatically. In the Web of Science Core Collection™, it has been cited over 5,900 times by researchers from 143 countries, with over 90% of citations made after 2000, more than 50 years after its publication date.

Figure 1. Citation patterns of Charles W. Thornthwaite’s article “An Approach Toward a Rational Classification of Climate” (1948)

An analysis of enriched cited references, a Web of Science™ feature that allows more granular examinations of the context in which an article is cited, reveals additional insight into this article’s research impact. Looking at the references of 752 citing papers with this context, nearly three quarters of citations leverage Thornthwaite’s paper to provide “basis” for the citing study, underscoring the importance of his work.

A macroeconomic concept rediscovered

The field of economics provides another interesting example of delayed recognition. After the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression, American economist Irving Fisher developed a theory to explain the economic crisis. “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions” was published in the first issue of Econometrica in 1933. It didn’t receive much attention at the time, partially because the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes were favored.

However, Fisher’s idea started to gain more traction among economists in the mid-1970s and may have influenced the responses of key policymakers during the 2008 financial crisis. A look at the citation pattern of Fisher’s article tells the same story. Out of 1,124 citations from the Web of Science Core Collection, just four occurred before 1980.

Optimizing the discovery of over a century of research

The Web of Science Core Collection serves as a unique gateway to over 120 years of past research. The world’s first citation index was conceptualized as an “association-of-ideas index” and documents the diverse ways that researchers apply and develop the same idea across disciplines.

The Web of Science Core Collection covers the deep intellectual roots and expansion of global study—from 1900, through huge advances in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s and onward into the present—enabling scientific work to transcend time and continue to advance discoveries.

Research has the power to transform society. As technology advances, previous discoveries take on new relevance and meaning. Throughout the full Web of Science Core Collection archive, sleeping beauties are waiting to leap to action and help researchers push the boundaries of knowledge.

What will you discover with the Web of Science? Find out today.

Interested in accessing the full depth of the Web of Science? Contact us.