As companies around the world increase their online presence, identification of IP rights in domain names grows in importance – especially among companies that are involved in e-commerce, providing goods and services using valued trademarks online. Accordingly, cases of cybersquatting are rising year-over-year.1

The rules that govern domain disputes vary in accordance with the extension2 of the domain name. Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) sets out the rules to resolve the disputes of domain names with generic top-level domains (gTLDs) and some country-code top-level domains (ccTLDs)3, while other ccTLD disputes are governed by their own dispute resolution policies.

There are currently six ICANN-accredited dispute resolution providers that adjudicate UDRP disputes around the world: the World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO), the National Arbitration Forum (the Forum), the Asian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Centre (ADNDRC), the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC), the Arab Center for Domain Name Dispute Resolution (ACDR) and the Canadian International Internet Dispute Resolution Center (CIIDRC).4 The supplemental rules, fees and the duration of the proceedings may differ from one to another, but complainants have the freedom to choose the UDRP provider they desire to use to hear their complaint about a domain dispute.

The focus of this article will be on the ADNDRC5 as well as the legal trends of ccTLD arbitration instances in Australia and India.

Asian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Centre (ADNDRC)

The Asian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Centre, with its four offices in Hong Kong (HKIAC), Mainland China (CIETAC), Malaysia (AIAC) and South Korea (IDRC);6 handles UDRP cases from all around the world, regardless of the nationality of the parties. The complainants can choose with which office of ADNDRC they will file the complaint. The fees to be paid when filing a complaint before an ADNRC office vary from $1,300 USD to $3,300 USD for disputes containing up to five domains, depending on the number of panelists requested.7

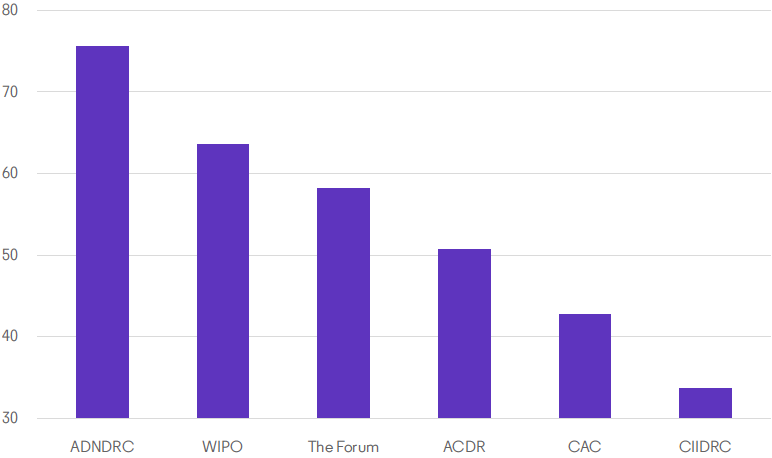

Although there are certain time limits and procedural rules for the UDRP disputes, the duration of proceedings varies amongst UDRP providers. In Figure 1 we illustrate the average duration of ADNDRC compared to other UDRP providers.

Figure 1: Average duration of UDRP proceedings by court

Source: Darts-ip

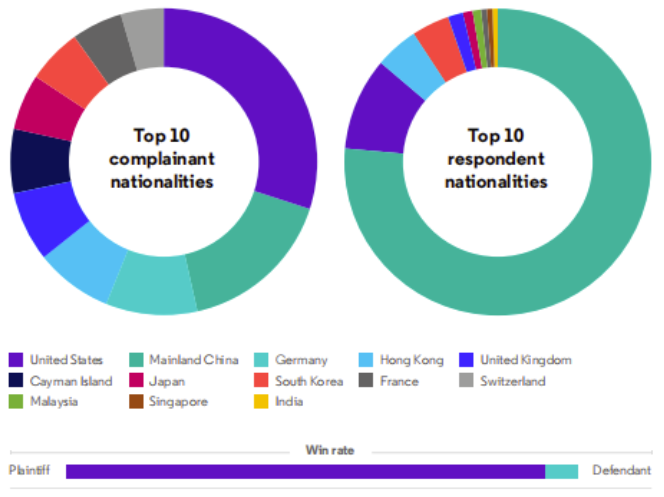

Certain factors determine the choice of a provider including filing fees, geographical proximity and average duration of time for rendering a decision. While the statistics in this regard reveal that cases before the ADNDRC may take longer, it’s still the preferred venue for Asian complainants and respondents. It is also worth highlighting from Figure 2 that for complainants residing in the Cayman Islands, the vast majority of cases relate to the complainant companies Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings.

Figure 2: Nationality/region of complainants, defendants and their respective win rate

Source: Darts-ip

The high number of respondents from Asia can be interpreted in multiple ways. First, complainants domiciled outside of the Asian continent prefer to file the complaints before ADNDRC when the respondent is located near to one of its dispute providers. Knowing that Mainland China has a record number of registrants in the territory8, such a result cannot be deemed surprising.

Secondly, the data suggests that complainants who are domiciled in Asia prefer to file UDRP complaints with a provider with panelists of the same nationality as the respondent. This also confirms that geographical proximity plays a significant role when choosing a UDRP provider.

Deeper look into auDRP and INDRP

Country code TLDs for India (.in) and Australia (.au) are governed by INDRP and auDRP respectively.

Although the filing policies and procedures may seem quite similar to UDRP, especially with auDRP since it is deemed as a variation of UDRP9, the main difference between some Asia dispute providers and UDRP providers can be found in the bad faith assessment for the respondent. While UDRP has a cumulative requirement that the complainant should prove the registration and use of the domain name in bad faith10, auDRP and INDRP take a different approach which finds either use or registration to be sufficient for a ruling on bad faith.11 Accordingly, arbitration instances have had completely different rulings to the matter when deciding on a cybersquatting case. Whereas in some UDRP cases WIPO has made detailed assessment on both use and registration in bad faith12, other panels have ‘inferred’ bad faith registration from the use itself.13 In both scenarios however, the cumulative requirement is fulfilled.

In contrast, INDRP and auDRP panelists have stopped the assessment if either use or registration in bad faith is proven,14 referring to the difference as: “Unlike the UDRP, the requirements of registration in bad faith and use in bad faith are disjunctive. It is only necessary for the Complainant to prove that the disputed domain name was either registered or used in bad faith. It is not necessary to prove both elements.”15

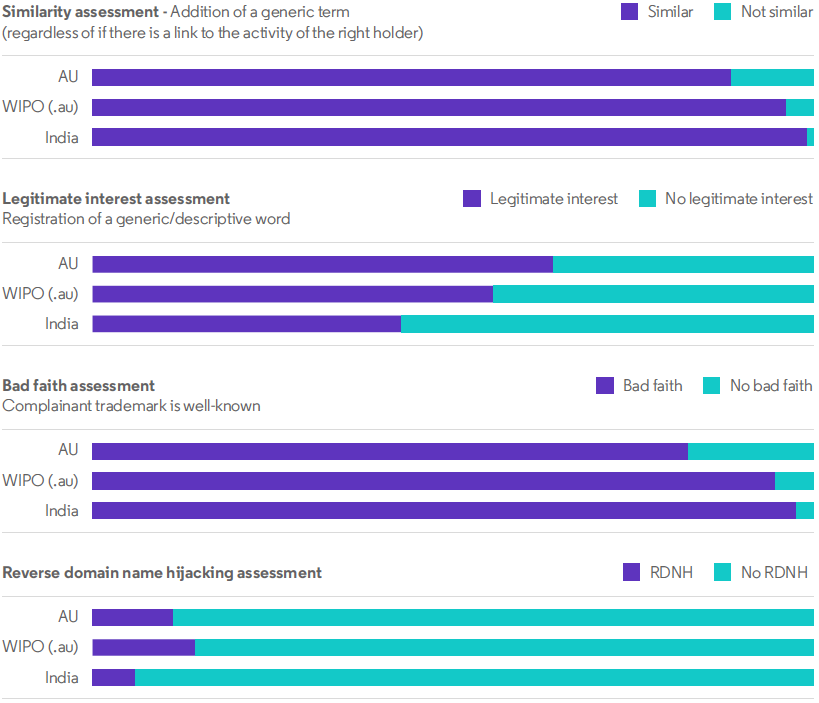

As per the comparison between INDRP and auDRP, although there is no strict distinction as mentioned above for UDRP, Australian arbitration courts, WIPO (for .au) and Indian tribunals have taken somewhat different approaches to domain disputes as well. Figure 3 includes some examples that highlight the difference between three different arbitration forums on the same subjects.16

Figure 3: Comparison of tendencies in different rulings for AU17, WIPO and .IN Tribunals

Source: Darts-ip

In the absence of clear, harmonized and strict rules for domain disputes globally, and in light of the irrefutable effect of jurisprudence on decision-making, it is more important than ever to identify distinctions between the approaches of the courts to the same or similar legal disputes. Having this in mind, we will see how the international nature of the internet will have an impact on the perspectives of ADNDRC, the Asian office of UDRP and the ccTLD dispute providers in the APAC region in terms of harmonization. Within this context, a helicopter view of the legal tendencies as well as the data revealing the different procedural and administrative statistics of the arbitration instances will support decision and policy-making.

References

- https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/statistics/cases.jsp

- Domain extensions are also referred to as Top-Level Domains (TLDs). They can be recognized in a website’s URL at the end. (i.e .com, .eu, .net, .club, etc…)

- The info of which ccTLDs are under the competence of UDRP can be found here: https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/cctld/

- https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/providers-6d-2012-02-25-en

- Asian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Centre

- https://www.adndrc.org/about_us

- https://www.adndrc.org/files/udrp/ADNDRC-Supplemental-Rules-for-UDRP.pdf

- https://domainnamestat.com/statistics/country/others

- https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/cctld/au/index.html

- UDRP para 4(a)(iii) see: https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/policy-2012-02-25-en

- INDRP para 4(iii) & auDRP para 4(a)(iii) see: https://www.registry.in/IN%20Domain%20Name%20Dispute%20Resolution%20Policy%20%28INDRP%29 & https://www.auda.org.au/policies/index-of-published-policies/2016/2016-01/

- darts-919-465-H-en-4: “(…) where a respondent registers a domain name before the complainant’s trademark rights accrue, panels will not normally find bad faith on the part of the respondent. Although this technically ends the matter, as this element of the Policy requires a finding of both registration and use in bad faith, the Panel also finds that the Respondent has not used the Disputed Domain Name in bad faith. It appears the Respondent uses the Disputed Domain Name for business or personal purposes and there is no evidence that this has been in bad faith.”

darts-174-463-H-en-4: “The Panel finds bad faith in the use but not in the registration of the Domain Name.” - darts-517-955-H-en: “The Panel therefore finds that the use of a domain name parking service constituted bad faith use of the disputed domain name (…). Further, the Panel also observes that the Complainant’s interest in and fame of the (…) trademark combined with the Respondent’s subsequent bad faith use of the disputed domain name would ordinarily be sufficient to allow the inference that the said domain name was also registered in bad faith.”

- darts-014-053-I-e: “...as the Respondent’s action to register the said domain name is not bona fide, therefore, the said registration is done in bad faith.”

- darts-508-724-H-en

- For this project, the decisions of auDRP providers which are located in Australia and DAU decisions of WIPO are taken into account separately.

- AU stands for the arbitration instances in Australia.