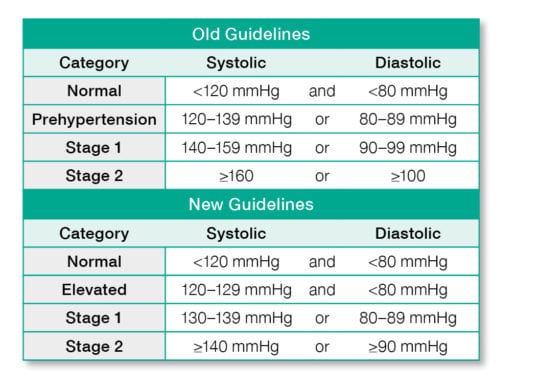

Towards the end of 2017, new guidelines on the appropriate range for blood pressure readings were released in a joint consensus between the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. These guidelines recommend a decrease in the systolic and diastolic readings that constitute what a healthy blood pressure looks like and a re-categorization of elevated readings. It’s estimated that these changes will mean new or increased severity of blood pressure diagnoses for over 100 million people in the United States. It is the first comprehensive review and overhaul of the guidelines since 2003.

These new guidelines, displayed in the chart below, generally recommend a reduction of 10 mmHg for both systolic and diastolic readings in each blood pressure category, though it should be noted that readings in the “normal” category have remained the same between 2003 to 2017’s updates. In addition, the term “prehypertension” has been removed and replaced with “elevated blood pressure.”

What does this mean for clinicians?

Practice changes resulting from these guidelines are placing a heavier burden on medical providers to obtain the most accurate blood pressure readings, so as to limit over- and underprescribing of medication. The guidelines recommend that in doctors’ offices, readings are taken with a blood pressure device that has a validated protocol for taking measurements. Though readings are typically taken using semi-automated cuffs, evidence is building in support of fully automated devices for maintaining standardization across hospitals and clinics.

Clinicians should also take into account that blood pressure alone should not be used to assess cardiac risk and inform treatment recommendations. Other cardiovascular risk factors—such as family history— should be considered prior to prescribing antihypertensive medications, which could mean that adults under the age of 65 with an otherwise low-risk profile for cardiovascular disease may simply be encouraged to adopt lifestyle changes to help lower blood pressure. In light of these new guidelines, physicians can consider a conversation with their patients about effective ways to control and maintain a healthy blood pressure.

What does this mean for patients?

These guidelines will impact many people—disproportionately those under age 45—and experts estimate that over one third of U.S. adults will now require antihypertensive medication. Because prevention and treatment recommendations can vary widely, patients should talk to their doctor about the implications of these new guidelines and how they may affect their overall health state and the care they receive. Some patients may want to discuss in-home blood pressure readings, which can help eliminate “white coat hypertension”—elevated readings that coincide with nerve-wracking visits to the doctor—and monitor whether or not certain blood pressure reduction tactics are effective. Ultimately, increased communication with primary care providers can provide the best mechanism for sound decision-making on behalf of patients regarding their blood pressure and overall cardiovascular health.